The International Energy Agency just released their World Energy Investment report - executive summary available here. As you might expect, the report shows some volatility within countries and technologies, but overall paints a picture of robust adoption of clean energy along what seem to be inevitable trends - dominance of solar, batteries and EVs. I’ve gone through the full report to extract what I thought were the most interesting tidbits, but the TL;DR points are as follows:

Massive and growing - Clean energy investment now over $2trn and continuing to grow. This spending is dominated by renewable energy, grids and EVs. These numbers are broadly consistent with BNEF’s investment trends report.

The Grid - investments have drastically lagged generation investments and it now represents the biggest bottleneck to expanding and decarbonising the power sector.

China, China, China - far from supply chains rebalancing globally, China’s scale has only increased its dominance in many areas (critical minerals stand out). The domestic oversupply is real.

Coal - is unfortunately not going away. China’s new coal plant investment has surged, although they are transitioning more to being used as peakers. India, although only building about one sixth of the capacity of China, are likely to have higher capacity factors as they are needed to fill demand growth.

AI for Efficiency - AI for process improvements in industrial applications represents a huge opportunity - estimated energy saving potential of >2,000 TWh over the next decade (for context US electricity demand about 4,200 TWh last year). That’s ~$80bn in savings based on average wholesale electricity price last year.

Hydrogen and CCS - this report paints a more optimistic picture than the equivalent numbers in BNEF, although the numbers are still small in the grand scheme of things. China is about to see a sharp increase in electrolyser investments. CCS could see a big uptick in investment (10x) if projects in late stage development are approved.

These data points corroborate some of the tenets we’ve been developing as our investment thesis at Keeling Capital. Growth in solar and batteries enabled by cost downs driven by China’s scale is a dependable trend. There are valuable businesses to be built serving those end markets, mostly software, but some hardware. Don’t compete on foundational technologies that China is manufacturing - that was solar PV in cleantech 1.0, more recently batteries and electrolysers. The grid represents a huge opportunity - it’s a major bottleneck for delivering incremental power, which price-insensitive hyperscalers desperately need (see our recent co-investment in Nira Energy alongside Energize Capital). There are going to be compelling opportunities where AI intersects with the physical world.

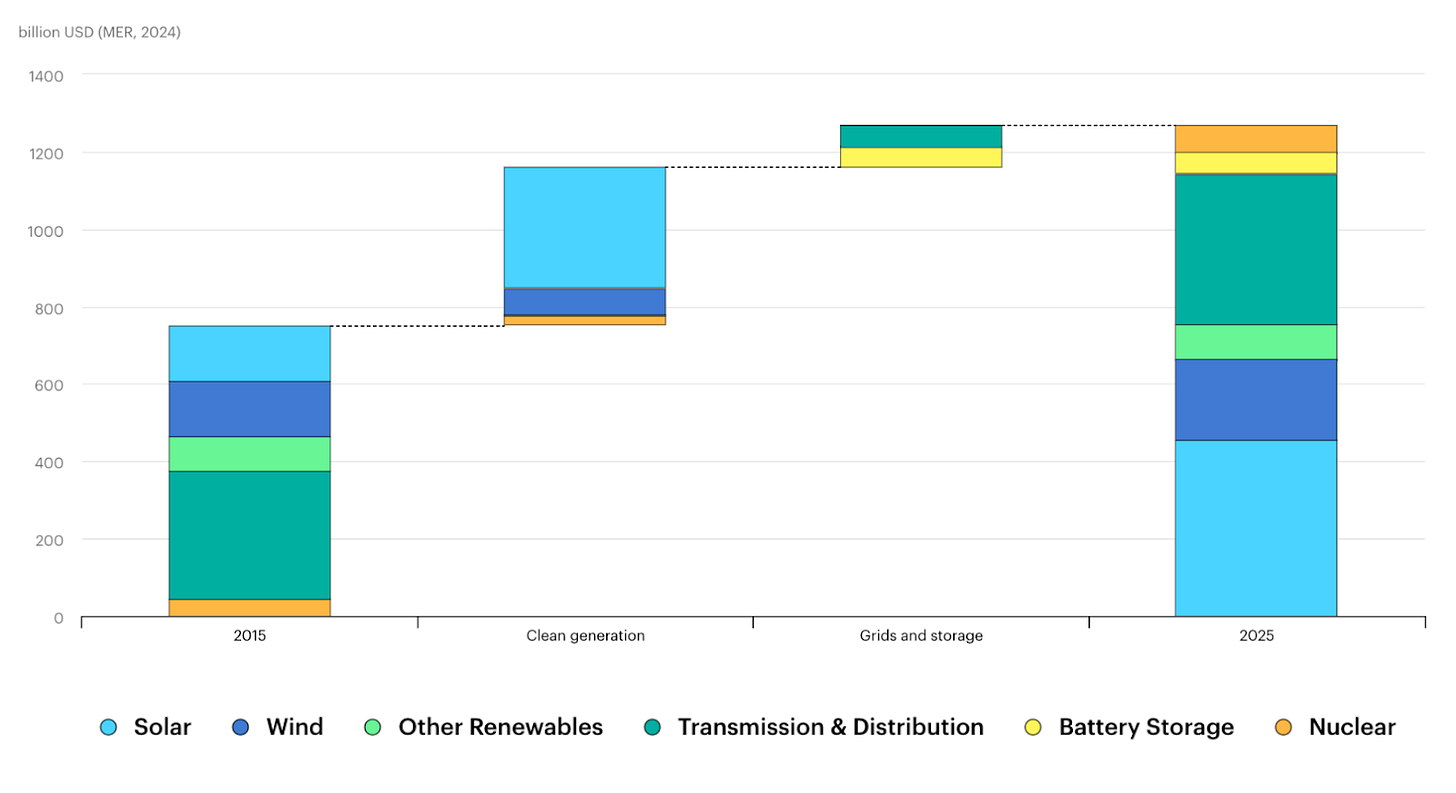

Investment in the energy transition is expect to reach $2.2trn this year, up from about $1.3trn five years ago.

This has largely been driven by the growth in solar. Spending on low-emissions power generation has almost doubled over the past five years, led by solar PV. Investment in solar, both utility-scale and rooftop, is expected to reach USD 450 billion in 2025, making it the largest single item in our inventory of the world’s investment spending.

And wind and solar together represent nearly the entirety of growth in generation investment. Solar PV and wind account for 98% of the growth in investment in electricity generation over the past decade.

Note that over the past 10 years, growth in generation investment has massively outstripped growth in grid investment. About USD 0.60 was invested in grids for every dollar spent on new generation capacity in 2016; today, that number has declined to less than USD 0.40 even despite declining costs for renewables and increasing costs for transformers and cables.

Clean energy generation, storage and power grids now represent 90% of investment in the power sector:

And investments in the grid are finally starting to tick up, now roughly $400bn per year. Grids and data centres: Over 90% of data centre operators now cite power availability as their top concern and nearly half place upgrading grid infrastructure as the most important mitigator.

Battery Storage: Investment in storage is rising rapidly, expected to be roughly on par with natural gas investment this year:

China

China, of course, is the heaviest investor in clean energy, and has moved its share of clean energy investment up from 25% to about 33% over the last 10 years.

The ramp in clean energy manufacturing in China continues to deliver startling cost reductions for mature technologies, with Chinese solar panel and wind turbine prices down 60% and 50% respectively over the last two years. But at least some of this is driven by intense and unsustainable competition from overcapacity. Check out the margins for China solar companies - no dark green dots on the right side of zero!

This overcapacity in China is opening the possibility of emerging markets forging a low-carbon development path. Pakistan alone imported 19GW of Chinese solar last year and is soaking up batteries. Of Chinese solar equipment exports, 44% by value made their way to EMDE (emerging markets) in 2024, up from 33% two years ago, and 41 different EMDE recorded their highest ever imports from China in 2024 even without adjusting for price reductions.

China is way ahead vs its own EV targets. In China EV sales nearly doubled in 2024 compared with 2022. To sustain this momentum, China has extended its vehicle trade-in policy into 2025. As a result, it is expected that around 60% of new car sales in China in 2025 will be electric – a milestone that was originally targeted as 50% for 2035 in the country’s 2020 roadmap.

Chinese manufacturers are going global. This doesn’t bode well for the aspirations of native OEMs, especially in Europe. In the last five years, Chinese EV and battery manufacturers have announced some USD 80 billion of investment to set up and expand manufacturing facilities in major markets, including Indonesia, Thailand, Brazil, Mexico and Türkiye. Solar manufacturers, long established in Southeast Asia, are also reassessing their overseas strategies, and looking closely at opportunities in the Middle East.

As for the bad news, China approved almost 100GW of new coal capacity last year:

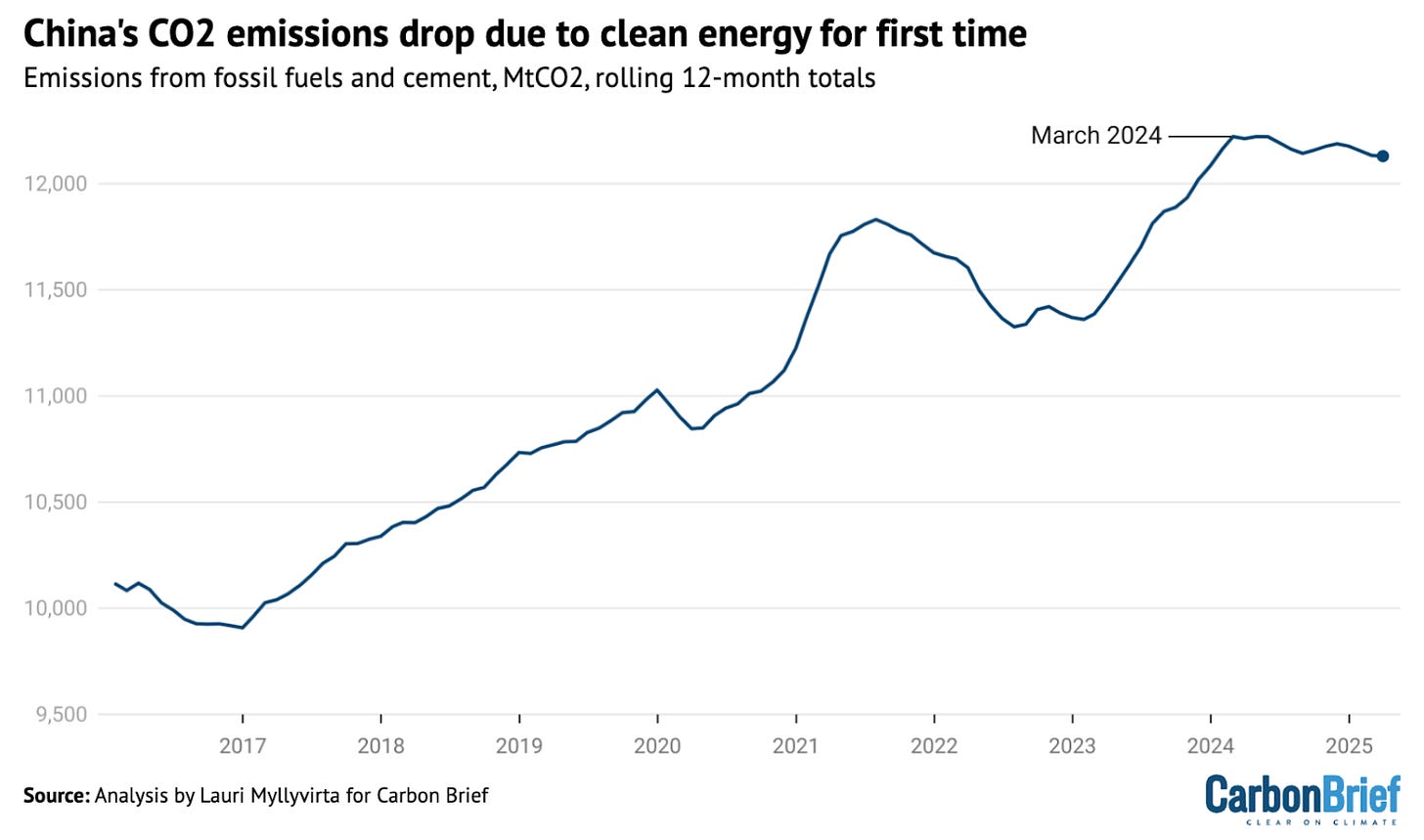

It isn’t absolutely clear how to think about this in terms of future emissions, since it seems we are just on the cusp of low-carbon power generation eclipsing electricity demand growth for the first time:

With deployment of low carbon continuing to accelerate from here (although with potentially some pull-forward in anticipation of market reforms that move projects towards market pricing, which came into effect for projects commissioned after June 1st):

But we do know from government policy that the expectation is that coal moves from baseload to a balancing function, so the coal build out may not be as disastrous for emissions as it looks on the face of it. Five-year plans since 2016 have sought to adjust the long-term role of coal from baseload to a provider of system flexibility and adequacy. For example, 300 GW of existing coal has been retrofitted since 2021 to meet new flexibility requirements. For the moment, [the utilisation rate of coal plants] remains around the levels seen over the previous decade, with coal power plants operating on average at around half their capacity nationwide. However, some new coal plants will be required to run at much lower utilisation rates (20% or less) and often with the main function of balancing electricity supply from intermittent sources.

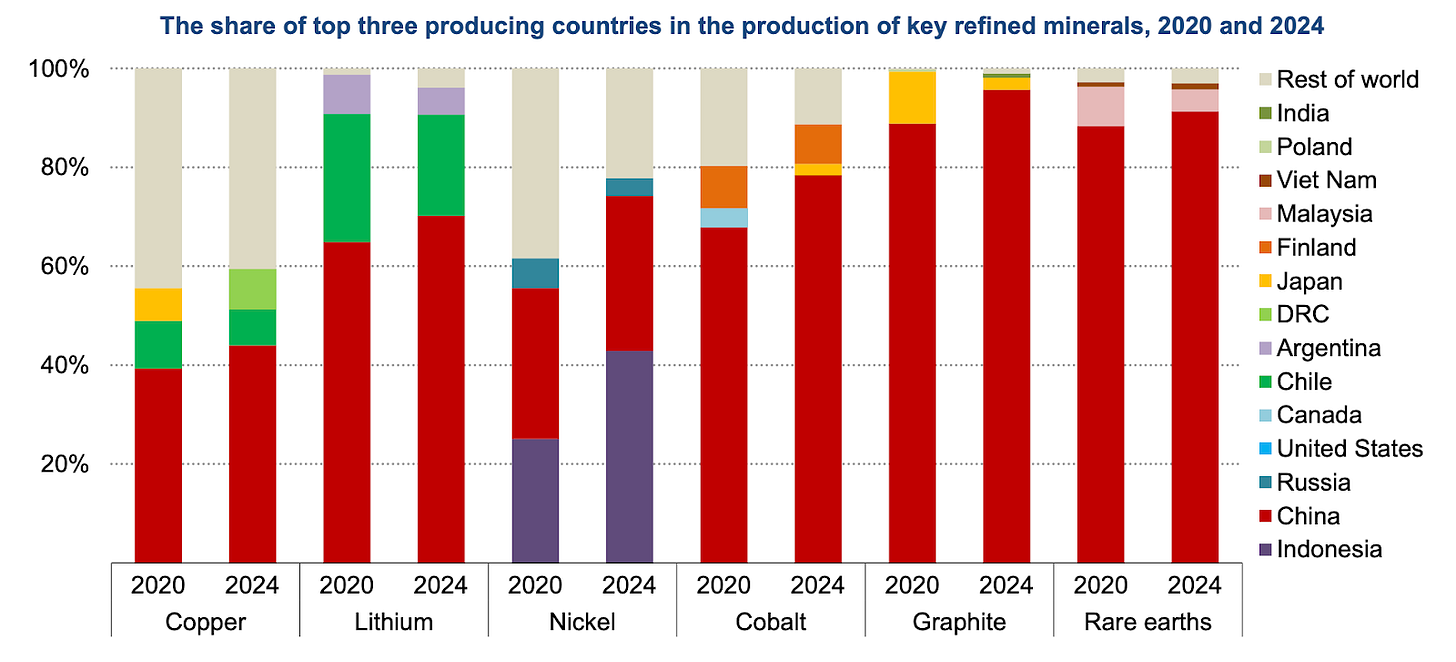

Critical minerals: The old adage about commodities that the best cure for high prices is high prices has been clearly demonstrated over the last several years in battery metals. In addition to new supply, innovation on the battery chemistry and manufacturing has reduced input requirements and largely pivoted away from NMC to LFP for batteries.

Innovators focussed on critical minerals in Europe and, particularly, the US, will likely need to rely on a geopolitical impetus for commercial traction if there is abundant supply of refined minerals from China, with their dominance only increasing in recent years:

Hydrogen: showing surprising signs of growth, given the masses of cancelled projects (due to the fundamental challenges of cost).

These numbers are still small in the grand scheme of things. Electrolyser costs in China are about a third of what they are in Europe. We just heard someone at a conference discuss how there is a huge build out of low-carbon ammonia production coming from China, which the US and Europe don’t have on their radar. We’ve seen how this story plays out.

Methane: In O&G production, 40% of methane emissions can be mitigated with projects with IRR greater than 15%.

Why no comments on the total pointlessness of all these growing initiatives? Not one can compete without subsidies. What exactly is the point?